Data in the Time of Crisis

1 July 2021

Christina Goodness, Chief, Information Management Unit, UN Departments of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs and Peace Operations

One year and 15 minutes later, I stepped away from the nurse’s table. I waited to see if there would be any vaccine reaction. After a year of remote work and crisis response for COVID-19, I sat there and took a deep breath, listening to the clicking of keyboards as the medical staff recorded the data and murmured amongst themselves.

Figure 1: Conceptual map of crisis information Figure 1: Conceptual map of crisis information |

Images came to mind of other crises I helped to respond to within the UN in the past. As a shepherd of some of the core data and information flows within the peace and security pillar of the Organization for the past decade, I’ve been privileged to have a unique perspective on the overall patterns of that flow. COVID had been no exception. During crisis, the pattern of information flow through our UN system has distinct design properties that had become more and more apparent to me. In a simple sense, I reflected, the closer to the center of the crisis, the faster the flow of data and the more tolerance for error and delay. And the inverse.

Managing a Policy-Driven Information Flow

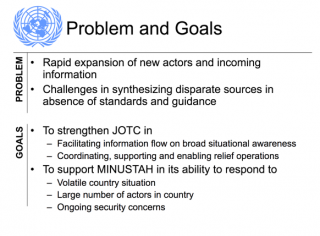

As an example, in 2010 I served as crisis surge capacity in the United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH), our prior peacekeeping mission in that nation, just after the earthquake that claimed more than 100,000 lives. The Joint Operations and Tasking Center (JOTC) of the mission was charged with convening the joint reporting for the crisis, linking the peacekeeping mission to the overnight influx of thousands of humanitarian actors which could be engaged via the Office of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) to serve the millions of harmed, displaced or deceased.

Pro forma, if a peacekeeping mission exists in a country, the head of mission is understood to be the head of the UN Country Team that coordinates with national counterparts. As an instrument of MINUSTAH, the JOTC was the central data hub charged with managing a policy-driven logical UN information flow. This included leading a daily central UN crisis situation reporting process, pulling inputs from all parties on ground, and culminating with a Situation Report to a Situation Centre in UN Headquarters. The reporting would be transformed into briefings to relevant backstopping offices, including the Secretary-General.

I sometimes visualized this flow in biological terms: the far field and mobile actors forming the capillary system, and sending sensory data to a centralized nerve and circulatory system, which then sent back and out coordination, support, and directives in some complex set of OODA loops.[1] But as in all crisis and field environments, best-laid plans and well-intentioned standard procedures often are laid waste by unexpected and exponentially consequential ground conditions. The reporting was regularly missing key sectors of information, but the needs were too urgent to start over. As long-time veterans would often say, we had to keep flying the plane while we were fixing it.

After I unpacked my sleeping bag in the Conference Room/Dorm/metal container at MINUSTAH LogBase, I reported for duty. Like a good business analyst (Lean Six Sigma Blackbelt), I then also began unpacking the evidence. The measurements of the information flow showed that there was a fast and furious cycle of minute-by-minute reporting coming in: numbers of tents needed and then distributed; discussions held between WFP, MINUSTAH and Member States; the locations where nighttime flood lights were needed to distribute food; the status and schedule of flights coming in on the airstrip that was 10 meters away from our makeshift office; the number of wash stations set up for every certain number of families.

Requests were routed as quickly and accurately as possible. But in the reporting process, the data was compiled into summary reports for country-wide decisionmakers. At that point, many details fell away, exact figures sometimes were corrected towards more verified numbers, and the timing slowed to a daily aggregated report.

Figure 2: Levels of data aggregation for decisionmaking Figure 2: Levels of data aggregation for decisionmaking |

As the same reporting was delivered even further outwards and upwards, this pattern became more distinct: the reporting reflected only the evidence that was most pertinent for critical decision making, trading comprehensiveness for prioritized insight and aggregation. And at the most senior level, the information flow informed monthly strategic reporting, or highly formalized biannual information sharing to the Security Council and General Assembly. The further away from the center of the crisis, the slower and more formalized the reporting cycle, the less tolerance for error, and the more it was expected to inform strategy. The expectations could be summarized in the Figure 2 graph on the right.

Staying Grounded in Known Facts

This inductive understanding allowed me to make specific recommendations to MINUSTAH, but also to provide much-needed perspective on frustrating in-the-moment information and data flow issues. In the middle of a physical crisis, staying grounded in known facts is critical. When key data on equipment, political dynamics, security, wash, food or shelter isn’t shared in a timely manner, there can be unpleasant to severe consequences, including to human life. However, ultimately, better outcomes are found with a bit of perspective on what kind of information can be generated and trusted for minute-by-minute tactical response, and what kind of information is truly needed to send up the information supply chain for strategic command.

Rapidly surveying needs for security within two hours of a food distribution can be done, but experienced staff know a degree of data error will always be part of emergency response. Agile field crisis response staff account for that degree of error, and for correction of that error, as soon as possible. In contrast, when all the security requirements need to be summarized for the last day, more verification is needed, so that the next 24-hour operational cycle can be better informed. You could roughly map this, it seemed at the time, to levels of organizational responsibility: front-line staff to tactical/line manager all the way to strategic. Like layers of an onion, at the center of the generative process, data is born and then matures outwards towards higher level significance.

As the Internet theorist Clay Shirky once said: “What we are dealing with now isn’t information overload, because we are always dealing with information overload, the problem is filter failure.”. The classic field-to-HQ situational reporting process added many filters to the flow and had delivered products of perceived value to recipients for many years. But as any engineer can tell you, if any flue or dam overflows, or if the rain is greater than expected, the cascading results can muddy the entire system. In MINUSTAH, a few simple calibrations increased the right Situation Report data between the mission and humanitarian partners, allowing for double verification. This then helped with better aggregation and reformat for higher level decision-makers. In the middle of crisis, rebuilding information flow from scratch is not possible. Urgent life-and-death issues prevail. But seemingly simple actions like clarifying terminology can massively improve data flow and have a measurable impact.

New Information Flow Issues

Figure 3: From the presentation to MINUSTAH senior management, January 2010 Figure 3: From the presentation to MINUSTAH senior management, January 2010 |

I recalled this as I was reflecting on this past year of pandemic and restrictions and what new information flow issues have arisen since then. In 2010 I thought that the center of the crisis was a physical place, a place of trauma and urgent response. This conviction was somewhat confirmed in later services provided to the UN Mission for Ebola Emergency Response (UNMEER) and to the Joint Mission of the United Nations and the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons in Syria (OPCW-UN).

However, even back in 2010 I was aware that the JOTC was one of several central nodes in a networked mesh of information flow; forming a core cluster, which included OCHA and the UN agencies, funds, and programmes, the Government of Haiti, the US, and other nation states. Now, in 2021, the COVID crisis has clearly had a moving center, or multiple centers, and the interdependency of global relations and networked response are clearer than ever. And we are not out of it yet. Finally, the value and misuse of real-time data in creating truth, or manipulating truth, during a crisis has come fully to a head.

I used to think of the information flow as like a supply chain, with that flow reflecting an “information lifecycle” that most information professionals are familiar with. The COVID crisis has challenged these assumptions. Is data ever truly fixed? Should it be? In a more democratized and decentralized decision network, are these different types of information for tactical-operational-strategic decisions still valid? Is the onion still the relevant metaphor? Or is the useful metaphor something more like a neural network?

The Secretary-General’s Data Strategy (un.org/datastrategy) is a vehicle for working through these issues so that we can leverage the massive knowledge, expertise and experience we collectively bring to our work, and leverage the huge data assets we have at our disposal. I urge all UN staff to reflect on their work and find ways to contribute to the conversations around the good use of data and evidence. By doing so we can continue keeping the UN innovative, and adaptive for the coming generations.

We are all in it together.

Food for thought. One year and 15 minutes later.

Note: The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations.

[1] OODA Loop: The operational cycle of observe–orient–decide–act used often in military practices. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/OODA_loop